NES ROM hacks and feminist discourse

Posted March 24, 2013 by Rachel Weil

Earlier this month, Mike Mika made headlines for hacking the classic 8-bit game Donkey Kong so that the roles of Mario, the hero, and Pauline, the damsel-in-distress, were swapped. Mika implemented the game hack to allow his 3-year-old daughter to play the game as Pauline. Much of the media coverage compared this touching story to a similar one that circulated last year about another daddy-daughter team: "Super Dad" Mike Hoye, who edited The Legend of Zelda: Wind Waker to cast Link as female, and his three-year-old daughter Maya.

I am happy to see classic game hacking alive and well, and I am happy to see these interesting projects getting widespread coverage. I think these dads' projects are great. However, I find the some of the news media's coverage and the corresponding online discourse troubling.

A new trend?

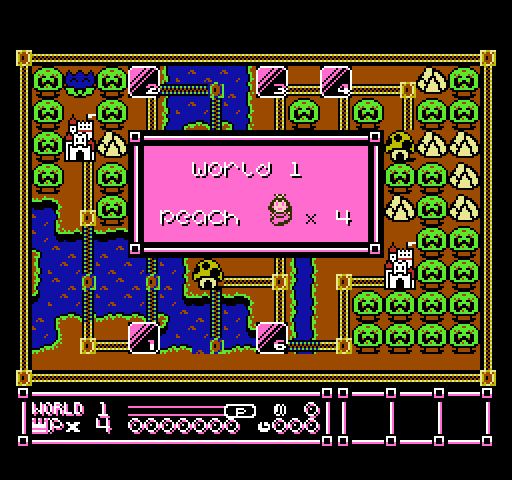

NPR stated that Mika's hack of Donkey Kong is not "the first time someone has done something like this, though the first time with such a classic game." If NPR means that this is the first time someone has hacked a classic game, then this, of course, is entirely false. NES ROM hacking—including the methods employed by Mika—are easily more than a decade old. And hundreds upon hundreds, if not thousands, of NES game hacks have been made in that time by both hobbyists and game piraters. But assuming that NPR meant that this was the first time that the gender of characters had been switched, or the first time that the rescuer had been replaced with the rescued, that too is false. How about the gender-hack of Paperboy to Papergirl, released ca. 2000? Or the incredibly unique damsel-turned-hero ROM Peach and Daisy: The Ultimate Quest, a Super Mario Bros. 3 hack released in 1999?

NBC, like NPR, seems to suggest that creating gender-bending ROM hacks is a new and exciting trend. "This may be just the beginning," they report, "A few dedicated hackers is all it would take and soon we could have 'Mega-Woman,' 'Blaster Mistress,' or maybe even 'Super Mario Sisters.'" Yet many of these games, too, have already been addressed by hackers. There was the ca. 2000 NES hack Mega Girl, for example. And prolific gender-hacker Mr. Dude made a staggering number of ROM hacks between 2005 and 2006, including Mega Girl 2, Mega Girl 3, Mega Girl 4, Mega Girl 5, Mega Girl 6, Super Momo Bros. 2, and Super Peach.

I myself have done similar hacks. Between 2002 and 2003, I created a hack of the NES game Super Mario Bros. called Hello Kitty Land. The ROM features revised graphics, palettes, game physics, and levels to situate the Mushroom Kingdom within the Sanrio universe. I also presented a gender-bending NES hack of Mega Man 2 called Mega Mam 2 as part of a live hacking demo at a conference in April 2012.

My intent in providing some of this historical background is not simply to call out some small error in an article as attempt to tear down an entire argument, author, or subject. Again, I think what these hackers did is great, both in terms of the ideas and execution. But when news outlets like NPR and NBC paint gender-hacking as a brand-new endeavor, it reframes much of the important context: the when, the who, and the why. I think, in fact, there is a specific reason that these stories made the news, and it has to do with anxieties centered on gender, inclusion, and harassment.

Reframing gender hacking

Because gender-hacking has been presented as a new phenomenon, the stories of Mika and Hoye seem to suggest that this activity is primarily done by dads for their daughters. "Daddy's little girlism" aside, I believe these stories have been made into popular news in order to create a narrative about men's role in reshaping hegemonic video-game culture. Last year (2012) was notable for several prominent "women and gaming and harassment" stories: those of Anita Sarkeesian, Jennifer Hepler, and Miranda Pakozdi come to mind. I would suggest that the recent popularization of these harassment stories has created a sort of anxiety around men's culpability in these scenarios, and that these pieces on "daddy hackers" aim to relieve this anxiety. They are heartwarming stories that present men as problem solvers rather than problem creators. These men use the technical knowledge that only they seem to possess in order to, as PC Mag reports, "empower female gamers."

One aspect of this kind of anxiety-soothing frame is a distancing from feminists and feminism, terms that many have been forced to grapple with or reject with respect to gaming. This quote from PC Mag's article about Mika's Donkey Kong hack illustrates this:

"By the time I started to catch up with all my social feeds, something insane had happened. This little mod exploded," he said, citing the feminist/anti-feminist comments made in response to his hack. "In my wildest dreams, I just expected a bunch of fellow coders to chat about the merits of the mod. I never expected it to ignite a gender role debate."

Mika promised it wasn't his intention to kick up women's lib dust; he just wanted to make his daughter happy. "I didn't set out to push a feminist agenda, or try to make a statement. I just wanted to keep that little grin lit up on my daughter's face every time we sit down to play games together," he wrote on Wired.

PC Mag emphasizes that Mika didn't want to "ignite a gender role debate," "kick up women's lib dust" or "push a feminist agenda," suggesting that women's rights issues are radical or extremist. (Note the choice of the verbs "ignite," "kick," and "push," casting feminism as aggressive or violent.) The notion that gender-hacking could "kick up women's lib dust" is a postfeminist suggestion that such dust has already settled and that to kick it up is to create a dirty mess of a debate that is already "over." A commenter on Slashdot posted an interesting comment in response to Mika's Donkey Kong hack: "This dad did what feminists can't be arsed to do, he worked long hours past midnight to change a game so it was more of her daughter's liking, instead of bitching about it for years without doing anything." This statement, too, pointedly situates the hacker dad in opposition to the "bitching" feminists, also serving to separate Mika's act from feminism.

The discourse centering on Mike Mika's Donkey Kong hack aims to present men as positive forces for gender equality in gaming while distancing them from feminism. These strategies help to relieve anxieties that might implicate men in the shaming and rejection of girls from gaming cultures. Additionally, the suggestion that this kind of ROM hacking is new and limited to loving fathers obscures a long and rich history of ROM hacking that includes women hacking games for their own ends.

Collection

© 2012-2023 FEMICOM Museum